Kokand Khanate in the late 19th century. Historical region in anticipation of change. Historically, the region of Middle Asia (Turkestan) since the olden days served as a bastion for the religious syncretism. As far as back the early Turk period (The Turk Kaganate, the Karakhanid dynasty) preachers, missioners, exiles of the different world religions, such as the Buddhists, Christians-Nestorians, Moslems- Sufis, Jalis etc, settled down here their sects and tried to propagate their ideology and cultural system among the local Central Asian population.

The memorial architectural complexes- the mausoleum of the Karakhanid in Uzgen city, the Burana tower near Tokmak city belonged to the ancient Balasagun) and the cave Buddhist temples are the monuments of this distinctive cultural and religious syncretism of the remote times.

The south of Kyrgyzstan, the present Jalal-Abad and Osh were under continuous influence of the Islamic clergy. The north of Kyrgyzstan moved away from the direct influence of the Moslem ideology territorially and ideologically.

In the 18-19 th century in the present Talas, Chui, Issyk-Kul and Naryn regions the Islam penetrated with the tide of the Moslem missionaries from Kokand Kingdom (Kokon Khan). The Kokand authority was in a great need of taxes, and first of all that had to be established among the new subordinates by the Moslem right and custom.

This issue mostly occupied mullahs and functionaries that penetrated into the north of Kyrgyzstan. In the period of the submission of the Kokand authorities, numerous strongholds were established on the lands of Kyrgyz that served as a bastion of not only for tax collecting and ruling of the Kokand Khan, but also for the Moslem clergy as well.

How

did the entrance into the sphere of influence of the Kokand authority reflected

on the spiritual and cultural life of the Kyrgyz? This was the dissemination of Arabic drawing. On its basis works on history, literature, and

traditional law (Adat), and Sanjyra (genealogical lines and genealogical map of

Kyrgyz) had been written. The numerous theological works were translated from the Arabic and Persian languages to the

Uigur, Kyrgyz and other Turkic languages. The upper society sent young

generation to the theological seminars and schools in Bukhara, Fergana,

Kashgar, Turkey and other famous Moslem centers. Through the Arabic

drawing the Kyrgyz began to enter into the strong zone of the Islamic ideology, its spiritual and cultural values.

In ethnological aspect of view, their connection with the Moslem world the Kyrgyz began expressing through both the traditional Sanjyra ( geneologies of different Kyrgyz tribes, clans and big families), and persons with mythological tradition of the Islam. Some characters of the Koran and Moslem legends artificially connected with the legendary founders of the Kyrgyz tribes. The Islamic ideology integrated the Kyrgyz intellectuals.

In the middle of the19th century, from the time of the joining Kyrgyz territories to the Russian empire, the Tatar mullah from the Russian Siberia came to the Kyrgyz. The local Turkestan administration took them willingly as the persons, who knew how to read and write, and speak both Russian and Turkic regional languages.

Tatars also were familiar with the customs and traditions of the region. Therefore, the Tatar mullahs became the mediators between the Russian authorities and the Kyrgyz. Besides that, the mullahs fulfilled their different duties of clergies, and participated and regulated the performances of various Islamic religious rituals.

It is interesting to note that once there was an attempt to convert the Kyrgyz population to the Orthodoxy Christianity. The Russian missioners began to visit different Kyrgyz regions. However, their activities were not widely accepted, and soon the Russian government gave up the idea to convert Kyrgyz to the Christianity as unfounded and hopeless. After that, the Russian rule officially considered Kyrgyz to be the Moslem population of the empire.

This is the brief history of penetration of the Islam in to the Kyrgyz traditional society. However, parallel with the Islam in the pastoral monadic society a powerful and ancient Turkic Kyrgyz religion existed and even dominated.

These was a worship of the Mother Umai (Umai Ene) and the Father Khan-Tengry, and the demonic Albarsty, the reverence of the ghosts of ancestors and animals-

“ongons”, and the fetishism of the different objects (stones, trees etc.) in the traditional religion of the Kyrgyz.

The acceptance of the Islam among Kyrgyz as the main religion nevertheless did not contradicted their ancient religion. We can see the synergy of the new Islamic and the old Tengry religion among the Kyrgyz. Generally, in the different aspects of the spiritual life and everyday practice one can observe the original fusion of the Islam with the traditional religious and philosophical system of the local population in Turkestan.

The likeness in the method of economic production and in the mode of life

as well as some parallels in the traditional ethic norms of the pastoral Arabic

nomads, who brought the Islam to the Middle and Central Asia in the 7th century, and the Kyrgyz

contributed to non-separation of the Islam as a philosophical, ideological, and ethic system. However, the Islam of Arabic conquers was transformed and adapted to the local culture and traditions.

Finally, the local medium disseminated the Islamic tradition of the Sunni doctrine. It promoted to centralization and constructing at the higher level of the local ancient cults and beliefs. The Islam took the traditional ideology as its subordinate elements.

Thus, under the influence of the Islam the local gods and goddesses were doomed to the further transformation. Therefore, Allah began symbolizing and identifying “Kudai”- God that had been revered by the Turk folks. “Arbak”- a ghost of ancestors became the linguistic synonym of “Ongon”, who were the spirits of people, as well as the ghosts of the sacral animals of tribes-totems.

Worship of the surrounding objects was included into the local variation of the Moslem religion, too. Further, they evolved into reverence of the masers (Mazar), stones, springs, trees, etc., and the Turkic Islam sanctified them.

The Islamic tradition of the holy objects, the worship of the holy images interlaced with fetishes of the original Turkic religion in the mythology of the Kyrgyz.

Therefore, the spirit of the Islam sanctified the names and the vital activity of the legendary founders of the Kyrgyz tribes. For example, legendary personalities of the Northern Kyrgyz -Tagay-Biy, Kyrgyz-Khan, Manap, and others.

The substance of the Islam replaced the powerful institution of shamanism (in Kyrgyz language “Bahshy”). The social and spiritual functions of Kyrgyz shamans fulfilled by Islamic Dervishes-Sufis. However, the shamanism as an ideological system (Bakshi in a variation of “Kuuchu”, “Duvana”) did not run counter to the Islamic mystical philosophical traditions. The rites of local shamanism with its elements of sympathetic magic (removal of bewitchment, affection of spoiling, change of name, amulets etc.) were incorporated into higher and structurally complicated cult of Dervishes of the Sufi doctrine.

The Islam surmounted the great distance in a space and the time and gained a foothold among the Kyrgyz in its transformed form owing to peculiar historical, economic and political reasons. The influence of the Kokand Khanate in further islamisation of the northern Kyrgyz in the 19-th century was powerful. The main aspect in this process played the economic issues of the state, especially necessity to collect taxes according to the rules and customs of the Islamic law. The Russian colonization fixed this process, and the Russian law recognized the Kyrgyz as a Moslem population of the empire. At present time, the Kyrgyz identify themselves as Moslems by tradition.

Dr. Chinara Israelova-Harjehusen ,a member of The Kyrgyz Taaryh Koomu. Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

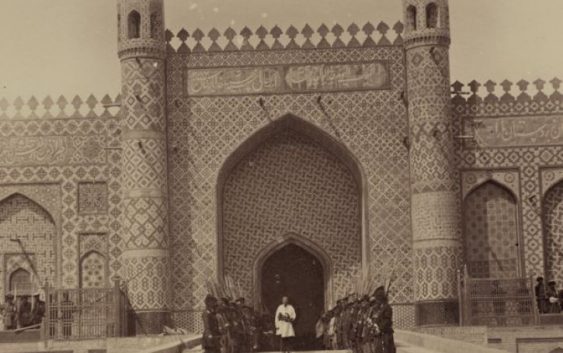

Kokand Khanate. Photos from the photo album «Turkestan Album», compiled by Alexander Kun, Nikolai Boegavsky, 19th century

Literature

Абрамзон С.М. Кыргызы и их этногенетические и историко-культурные связи. Фрунзе, 1990

Баялиева Т. Доисламские верования и их пережитки у киргизов. Автореферат канд.дисс., Ленинград,1969

Басилов В.Н. Культ святых в исламе. Москва, 1970

Бартольд В.В. Киргизы. Исторический очерк. Соч., Т.2.,Ч.1., Москва, 1963 Валиханов Ч.Ч. Собр.,соч.,в пяти томах.Т.1.,Алма-Ата, 1961

Валиханов Ч.Ч. Записки о кыргызах. Собр.соч.,Т.2, Алма-Ата,1985

Венюков М.И. Очерки Заилийского края и Причуйской страны, из «Записок Российского Географического Общества», СПб., 1861

Домусульманские верования и обряды в Средней Азии. Москва,1975

Исраилова-Харьехузен Ч.Р. Традиционное общество кыргызов в период русской колонизации во второй половине 19-начале 20 века и система их родства. Бишкек, 1999

Мамаюсупов О.Ш. Вопросы(проблемы) религии на переходном периоде.Бишкек,2003

Молдобаев И. По следам религиозных верований кыргызов с древнейших времен и до наших дней. Бишкек,1999

Никишенков А.А. Обычое право казахов, киргизов и туркмен.Москва,2000

Чарыков Н.В. О влиянии ислама на развитие Средней Азии во второй половине 19 века. В «Вестнике Томского государственного

университета.История. Вып.,4(20),2002

Центральная Азия: Ислам и государство ICG.Доклад по Азии, № 59, ОшБрюссель, 2003

Ashymov, Daniyar. The Religious Faith of the Kyrgyz.in “Religion, State &Society”,Vol.3, No. 2, 2003